Daily Life and Slow Travels in Mainland China

Food, soul, and city walks from a Chinese American's visit.

After traveling in Japan, I spent a lot of time in mainland China, in places large and small. I wanted to experience daily life and level up my Chinese skills. Even though I had hated learning the Chinese language earlier in my life, I wanted to struggle again and find a side of China that I truly loved. At the same time, I kept in mind my possible plans for relocation.

When Asian Americans think about China, it’s often a 2 week trip to Shanghai and Beijing, plus maybe a visit to the family village (if they have one) to say hello to grandparents and uncles. This can sometimes lead to a skewed view of what China is, especially if they’re visiting the country with their parents as the tour guides. The “family trip to China” can really cause them to miss out on understanding some of the new developments, hidden gems, and exciting youth culture of this bustling modern country.

During my journey, I traveled from Tier One cities to small towns in Mainland China. I visited Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Chengdu, Chongqing, Xi’an, Inner Mongolia, and some family towns as well.

New Hope for an Old Language

Learning Chinese in the USA is, in my opinion, not only useless but greatly discouraging. Normal life in America is conducted in English, and speaking Chinese doesn’t open up any particularly new or exciting opportunities, outside of an occasional extra serving of food from a restaurant owner. ABC’s who attempt to speak Chinese with first-generation immigrants usually find out that the first-gens prefer to speak in English, and they might even react with outright hostility and disappointment when a Chinese American’s Putonghua isn’t “good enough.” The Chinese American ends up regurgitating the language from textbooks and language classes in an isolated corner, constantly being held to an impossible standard of fluency, which is a dead end that doesn’t allow for engaging with the living and authentic culture of Chinese people.

But in China, the landscape is completely reversed. Your language skills will be the key factor that allows you to meet new friends or puts you on the wrong airplane flight because you misread the ticket details. China is a practical, high-stakes language environment, and the Putonghua-speaking traveler gets to unlock new doors that lead to exciting touristic adventures. Chinese locals don’t speak English very well, if at all, so when an ABC speaks to them in their language, they react with joy and happiness and are all-too-eager to ask questions and become new friends. Many of them have never met Chinese Americans before, and they might ask a lot of questions about what the USA is like.

Years ago, when my Chinese was much worse than it is now, I got in a taxi and heard the driver speak very quickly in Chinese with a regional accent. I asked him, “Could you please say that a bit slower…” and he brightened up, got excited, and asked me where was I from and what I was doing in China. As a result, we got to enjoy a really delightful and engaging conversation. In a funny way, Chinese Americans who suck at Chinese get criticized and berated in the USA, but in China, the bad accent and linguistic ineptitude becomes a unique feature that can open the door to many new connections.

Don’t get too used to the special treatment, though. Once your Chinese officially reaches a native-sounding level, talking to local people will sometimes cause them to think that you’re a stupid unclever person who speaks too slowly and doesn’t understand anything that’s being said, and you would need to tell them that you’re Chinese American (美籍华人 meiji huaren) if you want to activate your special “foreigner privileges.” It’s a good problem to have, though, since at that point your Chinese would be good enough to basically survive in the mainland!

Most of the local apps in China do not have any support for English speakers. So you need to get good at reading, or guessing what things mean, and you can support yourself in emergencies by taking a screenshot and passing it through Google Translate or looking up unknown words in an e-dictionary like Pleco. I still remember my own shock when I ordered “牛…面” thinking that it would be beef ramen (牛拉面 niu lamian), only to see that it was actually bullfrog noodles (牛蛙面 niuwa mian) with spicy bone-in frog meat on top. I’m a pretty adventurous eater, but this was too much for me, especially at 3 am on a Friday night.

Some people feel intimidated to travel in China due to lack of Chinese fluency, but I think this shouldn’t stop them. If learning Chinese by yourself in the USA hasn’t helped you in the past, then what makes you think it will get better in the future by avoiding China? Reading the digital apps can be pretty overwhelming, but for learners, I suggest glancing at the sentences at a high level and seeing what characters you recognize in order to take a guess at the general meaning. In the worst case, you can get around using translator apps, which is indeed what some eternal expats do, some of whom share absurd stories of living in China for 5+ years without speaking Chinese. Chinese Americans are certainly better equipped than these guys and should not gatekeep themselves. If you have a heritage foundation in Chinese — even if it’s basic, or you only understand words but can’t repeat them, or you struggle to read — you’ll get way better at Chinese if you put in even a little effort.

The Local Treatment

Ordinary Asian Americans essentially get treated as local Chinese people before they even open their mouths. And once you start speaking, as long as your Chinese is at an intermediate level, the local people still basically assume you’re some kind of Chinese, even if you’re actually Korean. I had one person tell me: “Wow! Your Putonghua is so good for someone from Hong Kong!”, so I had to tell her that my parents are actually mainlanders. The main exception to this rule is Chinese people who have serious experience with international life (e.g. grad students who studied abroad or workers employed at international companies) — with them, it will probably be more enjoyable and productive to just speak in English.

You might get some funny looks speaking what you consider to be proper Putonghua in Tier Three cities. In these places, other dialects are extremely prominent, and locals, especially the older generation, speak to each other in the regional language. When I visited a convenience store in a small town, the storekeeper was shocked to hear my Chinese and asked me where I’m from, and what brought me to the area. Even after explaining to her that I’m a Chinese American, she just assumed that I was a local Chinese who worked in an American company, and was friendly and kept asking questions about my daily life. Another time, some older people were shocked to hear my “textbook style Chinese” and said, “Your Chinese is better than mine!” For them, speaking “proper Chinese” means avoiding dialectal pronunciation, but for Chinese Americans, they’re simply reciting the academic pronunciation that they learned in school.

One benefit of the local treatment, in my opinion, is that “administrator guys,” like subway attendants and security guards are usually pretty sympathetic to you and don’t treat you as a weird foreigner. If, for example, you get some sort of strange error that shows up because your ticket wasn’t registered properly, or perhaps your face ID didn’t work with the entry scanners, people seem to be quite accommodating and extremely willing to help you.

Normal Life, East Asian Style

It might sound obvious, but China is an East Asian country and it is designed to support an East Asian type of lifestyle. In the United States, Asian American people sometimes feel like they’re walking uphill all the time, with a constant headwind that stops them from moving forward: advertisements on billboards don’t cater to Asian people, Hollywood movies don’t feature East Asian values or actors, and food (while enjoyable) isn’t optimized for East Asian palates. For such people, visiting China feels mindblowing because all of a sudden, the entire society and culture is organized in a way to make you feel like a satisfied family member in a house that belongs to you. Walking around, everyone has East Asian fashion, attitudes, and preferences, and the question of your life in this environment isn’t about your race but rather your personality.

I also saw quite a few young people wearing Hanfu (medieval Chinese clothes) — which you can try on yourself at a Hanfu rental shop — and even active Buddhist monks wearing their clerical garments on the subway. Historical tourist sites in Xi’an also had live theatrical performances covering ancient Chinese themes, which were quite engaging and impressive.

If you like East Asian media — not just Chinese dramas and manhua but also anime and K-Pop — there’s plenty of it in the larger cities. It’s extremely refreshing to walk around and see Asian-style media consumerism everywhere, not as a niche hobby but as something that is normalized for ordinary young people. In Chinese cities, I saw product collaborations with Genshin Impact, Link Click (Shiguang Dailiren), Gintama, Persona 5, and even an unexpectedly large number of casual anime cosplayers when there didn’t seem to be events going on. It was also easy to find native Chinese manhua and Chinese translations of Japanese books.

Old Culture in a New Era

It seemed like every city I visited had a traditional, or neo-traditional, district that was full of beautiful, recently-renovated Chinese style architecture. These places were deliberately set aside by local governments, I imagine, for the sake of tourism and cultural preservation. They had gardens, lakes, old-style buildings, and bright lights that illuminated the entire area so that they could be enjoyed well into the night hours (which Chinese locals happily do). As a Chinese American traveling in China, I felt that it was a joy to be able to casually enjoy East Asian architecture with great ease, without deliberately seeking it out, quite often in my daily life. Oftentimes, you could simply walk around and casually bump into a beautiful Chinese pagoda, or step into an ancient-looking teahouse, a place that would be exciting and exotic if it existed in New York but simply commonplace in the country of China.

Although America has Chinatowns and Chinese communities, I would say that the best Chinatowns do not surpass the beauty of even a 4th Tier city in China. American Chinatowns are somewhat shabby and dirty, resembling what China looked like in the 1980s, and if in the cases where they are upscale and fancy, they look more like a flattenned, modern consumer shopping center (like Sanlitun in Beijing) rather than something that embodies East Asian culture. There isn’t anything like the traditional-style neighborhoods that we see in modern China.

These traditional-style districts would have many food vendors selling snacks, but outside of maybe one or two local specialties, I often saw the same foods repeated again and again: fried potato towers, grilled squid, and meat skewers — even across totally different cities separated by vast distances. It was kind of a disappointment, especially compared to Japan where their touristic districts always focused on local ingredients and local specialties.

One negative aspect of the Chinese cultural renovation efforts is the generally lower quality of museums that I personally encountered in China. With the exception of the Shanghai History Museum, which I loved tremendously and was a major highlight of my trip, most of the museums that I saw in China were a bit disappointing. They had pottery and relics, sometimes talking about particular historical facts, but rather than explaining the grand ideas and high-level thoughts that caused history to move forward, they focused on the nitty-gritty material details of this year and this place, that a certain thing was discovered in such-and-such city, what its chemical composition was, over and over again, without really adding any deeper meaning to it. I was particularly flabbergasted to see a small exhibit dedicated to a local Chinese author, and yet not a single word of the man’s original writing was available on the signs, nor was there even an explanation of the topics that he wrote about!

Walkable City Life

In China, big cities have designated “pedestrian streets” (步行街 buxingjie) that are absolutely mandatory to visit if you like walkable cities. These areas are densely concentrated with various activities and are filled with people from daytime to the wee hours of the night, and most importantly, they are set up so that the ubiquitous electronic scooters and cars are banned from driving through. Here, you can grab food, do some shopping, get a coffee and milk tea and cocktail, visit a spa, and gaze out on the streets and do some Chinese-style people watching. Modern Chinese cities I visited were quite active at night, and there’s a lot to do even after 9 pm on weekdays, when white collar employees get off from work.

Similarly, you’ll also see something like a “food street” (美食街 meishi jie). I don’t know what to call them, but it’s a row of restaurants that open out towards the public where you can line up and find something delicious to eat, interspersed with other places like convenience stores, barber shops, and mobile phone stores.

The lower tier towns, as well as the lower tier districts within the T1 cities (e.g., the old school less-commercialized parts of Shenzhen), are also extremely walkable in an organic way. These towns don’t have metro systems and most ordinary people use cars, scooters, and bikes to get around. Maybe it’s because these towns are older, “less advanced,” and don’t have top-down city planning that they end up becoming more walkable out of pure necessity. In the lower tier areas, it’s also easier to find street vendors and food stalls, which seem to have been restricted or banned in the T1 cities, and you’ll also see people randomly hanging out, smoking cigarettes or eating meals on small tables.

With that said, Chinese cities are not perfectly walkable, and I was sometimes frustrated when I got to a new location and had to figure out where the bustling activity was supposed to be. In the post-covid era, some cities do not have as much activity that “spills onto the streets,” such as the more westernized parts of Shanghai or in the more advanced districts of Shenzhen which can feel quite vast and empty at times.

In mainland China, outside of those designated “pedestrian streets” and “food streets,” it sometimes feels like you need to have a purposeful intention before walking into the domain of an activity. A restaurant might be a true local gem and really popping with energy, but you sometimes cannot see that from outside due to the building which has large walls that stops you from sneaking a peek. You have to walk inside, go past the lobby area or even take an elevator, and look inside to see how active it is. It feels like many events are “enclosed” within their own little worlds. Sometimes, you even have buildings that are quite crappy and dilapidated from the outside, only to see that it transforms into a luxurious high-class restaurant inside.

I felt that Beijing was a particularly egregious example of this, and absolutely not walkable nor friendly to the improvised tourist, where the city is set up in a way that you have to visit a specific district with a plan in mind, pick a venue, followed by lots of trees or houses, then find another venue. It reminds me a bit of Los Angeles, with walkable bubbles that are separated by vast distances. There’s often no easy way to walk from place to place unless you’re actually in a shopping street or hutong. In contrast, Shanghai was probably the most walkable T1 city in mainland China that I visited, with a very dense metro system that perfectly connects the city together, but it still had a bit of this “enclosement” phenomenon outside the pedestrian streets. Although I didn’t stay very long in Xi’an and Chongqing, I felt that these two cities had a great blend of walkability, new city mixed with old culture, that felt similar to what I loved about Tokyo.

It’s worth noting that normal Chinese people live in mega-apartments, even in the lower tier cities, which means sometimes you’ll see entire blocks of giant rectangular apartment towers. I struggled for a long time to articulate why I felt those buildings looked so strange, and I concluded that it was because each apartment has its own giant A/C unit that’s just sticking out the window, causing the entire building to look like a brick. This, to me, is a little sad since it might look nicer to have small single family houses in the residential areas, like Tokyo or Taipei. Alas, this is how the modern government decided to design the cities, and at least they succeeded at keeping rental prices extremely low.

Cocktail Chats in China

In China, I tried to visit bars in order to practice language, meet new people, and drink some nice cocktails. My attempts were successful, but it required effort and attention. A lot of bars that are rated highly on the Chinese apps are not cozy or conducive to conversation but rather large, luxurious spaces that tried to imitate western venues but made them bigger and fancier. In these places, the drinks were delicious, but conversations were few, and most locals just came in with their pre-existing groups of friends. It was usually more productive to find smaller bars where people mingled more often, and I got to have really cool and deep conversations with local Chinese people and some expats. One of my favorite adventures was talking with some truly regional people at a Third Tier city, getting upgraded to “brother” (兄弟 xiongdi), and then visiting a karaoke place after. Another interesting feature was an entire apartment-style building that was actually filled with different bars and shops in each “room,” and opening a different door would take you to a different small tavern.

I couldn’t help but compare these Chinese bars to the ones that I saw in Tokyo and Osaka. In Japanese cities, the bars seemed to be way smaller, and conversation between random strangers is an expected part of “common courtesy” that, in hindsight, supercharged some of my chats with local people. In China, it’s more of a struggle to find this type of experience. Incidentally, the price tag for a cocktail in China was 99 RMB (14 dollars), which did hurt a bit compared to the 600 yen (5 dollar) price tag of a lemon sour in Japan.

Digital World

In order to survive in mainland China, you need to plug into their digital app ecosystem, including but not limited to WeChat, AliPay, transportation apps, map apps like Gaode, package and food delivery apps like Meituan, social media like Xiaohongshu, and a VPN if you want access to western internet (which you probably do). It’s a real pain to set these up for the first time, but after you succeed, you can experience daily life within China without any hindrance.

If you really want to slow-travel for more than a month, it’s suggested to go to a mobile phone shop and register your passport to get a local Chinese phone number. With this, you truly unlock almost anything you need when it comes to digital services. There are some apps that will still prohibit you due to not having a national id (身份证 shenfenzheng) but those are fairly rare.

Restaurants will usually have QR code menus where you scan, browse, and pay, but I personally found this to be surprisingly non-magical and clunky, as the internet connection can be quite slow indoors, and I prefer to have physical menus for looking through foods. With that said, it was nice to be able to order stuff without having to learn how to pronounce it, and it made eating out with multiple people way easier, not needing to do excessive coordination for the orders.

Even though modern China is a digitalized world, the public internet that you get at coffee shops and hotels is not fast at all. This became a continuous pain point whenever I wanted to take my laptop out and do some work in a venue. In fact, the quality of public internet actually seemed to go down compared to when I visited before covid. It seems like local people tend to just rely on their smartphone hotspot data when they need high speed internet in public locations.

Cost of Living

For people earning a US-dollar salary, mainland China is an extremely cost-effective place to visit. A Chinese uncle told me: “Just take the American price and replace the $ sign with ¥.” A restaurant meal costing $20 in the US would be ¥20 in China. An Uber ride for $15 is ¥15 in China. I felt that this rule of thumb worked pretty well, and combined with the current exchange rate, this generally means that American dollar-owners get an 85% discount on everything in China.

In practice, this means that you can feed yourself for less than $5 for an average breakfast or local meal, and $500/month is more than enough for a basic Airbnb-style apartment in a Tier Two city. Food delivery services, the DoorDash equivalents in China, actually work and are extremely economical, and you can get quick food for 10 USD without having to worry about tips and delivery charges. Even a fancy western restaurant meal still ends up being way cheaper than the equivalent in the USA, capping out at around $30 US per person in my experience.

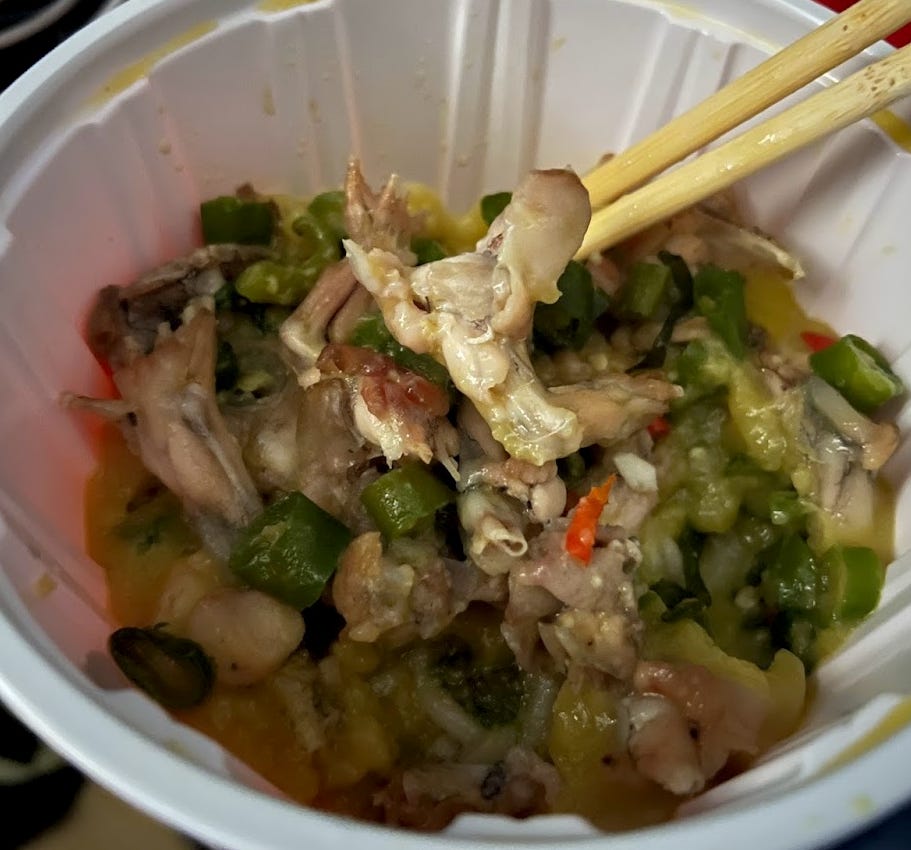

Chinese Face, American Belly

Mainland China is a food-lover’s paradise, where you can get extremely tasty local eats for a very affordable price. In the United States, I had never really considered myself particularly fond of authentic Chinese food, but in mainland China, I was greatly surprised at how delicious everything was and how real the food tasted. For example, growing up in the USA, I had always considered Shanghainese fried buns (shengjian bao) to be pretty mediocre, with skin that tasted rubbery and meat that felt sort of like gray synthetic meatballs. But in Shanghai, I was surprised at how tender and delicate the skin was, the juiciness and flavors of the interior broth, and how “real” and wholesome the meat tasted inside.

There were also many unique Chinese dishes, combinations that I had never seen before in the US nor even heard of, like crab roe noodles, dumplings with eggs, and meat wraps that were full of savory pork belly. For protein lovers, you can easily get a heap of meat skewers for pretty cheap and eat like a Mongolian prince.

There’s also no shortage of foreign food either. You can go to interesting European or American themed restaurants, pay a little bit more than average (but still cost-effective compared to the US), and enjoy some fancy Western-Chinese food. Sometimes, just the feeling of being in the venue adds some joy to the experience.

One exception: In my opinion, the Japanese food was pretty bad in China, particularly the sushi. I was genuinely surprised since it was even worse than the Japanese restaurants in America, which ironically are usually operated by Chinese people. Not sure what happened there, considering that even years ago, I had enjoyed really delicious sushi in Beijing, and that Japan is just a 2 hour flight away from Shanghai, but perhaps the recent concerns with water quality led to a decreased quality of imported fish. It was also pretty noteworthy to me that the sushi (even at casual restaurants) in both Hong Kong and Taipei were superior to the sushi in Shanghai.

Western fast food, like KFC and McDonald’s, is very good in China, with many of localized Chinese aspects, like rice porridge for breakfast, meat wraps, mala-flavored burgers, and durian-flavored pizza (don’t knock it until you try it). I ate this junk food pretty often, because it was so convenient, and I also wanted to try every local variety of fried chicken before leaving the country.

When you visit China, you might be tempted to eat platefuls of tasty food and local specialties, becoming overweight and possibly obese, which ironically no longer allows you to live in China since everybody is very thin.

Mandarin Oranges and Other Fruits

The grocery stores in mainland China were filled with fresh produce that was extremely tasty and presumably nutritious. I began to develop a habit of eating fresh fruit, almost all the time, and I genuinely looked forward to passing by local fruit vendors in order to see what newly-harvested goodies they had in stock. I noticed that when I returned to the USA, my natural inclination to eat fruits and vegetables fell off a cliff, since the fruit in American stores just doesn’t seem to be as ripe.

I’ll never forget the oranges that I ate, which were so plump, sweet, and juicy, with skin that easily peeled off without any effort and an intense orange flavor inside. I never was able to find equivalents in America. It is no joke to say that I would sometimes eat 10 of these oranges in a single sitting as a full meal. I also got packaged durian pretty often, which was slightly expensive, delicious, and packed with custardy goodness. Local grapes were also very sweet and crispy.

The eggs in China were delicious, tasting very meaty and wholesome, with bright orange yolks that I’m quite sure were not artificially dyed, as sometimes happens with “pasture raised” eggs in the United States. You can collect them in a manner that was somewhat foreign to me as an American, where they are sitting plainly and unrefrigerated in the store, stacked on top of each other like rocks.

One thing that was some difficult to find was beef steaks, but you can buy frozen steaks (which are smaller than their western counterparts), and they are a bit more expensive than other Chinese products.

Western Comforts in the Supermarket

The supermarket in Chinese towns (even small ones) is quite “super” indeed, and you can get almost anything you need that you miss from the west. Western foods, toiletries, medicines, cooking oil, foreign wine, can all be found. If you really need to have a particular type of western-only good, or even something from Japan or France, you can usually find it at the supermarket, which is huge and has many sections. In particular, I felt that the typical supermarket in China had way more European and Australian goods than supermarkets in the USA.

One exception is vitamin supplements. It was a pain to find good ones at the Chinese supermarkets, although perhaps I was looking in the wrong place as I didn’t dive too deeply in the medicine stores. I think this could be an example of stuff you should bring from the west, or try to find on Taobao.

Convenience Stores and Coffee

Like Japan, China has many convenience stores, which are some of my favorite places to visit. I encountered two types of stores: (1) the old Chinese style that has cigarettes, 2% beers, chicken feet, boiled eggs, and duck tongues; and (2) the Sino-Japanese style which is bright, white, clean, with foods like sandwiches, rice balls, and boiled meats that are less exotic and more western-friendly.

I preferred the second type of store and loved to browse the goods even if I didn’t want to buy. I really enjoyed the boiled-chicken-in-a-bag, canned cocktails, and some strange concoctions like shelled clams in chili oil. It was surprisingly tough to find seltzer water in some cases, and it was almost impossible to find canned black coffee, as the coffee options all had milk or sugar in it. This would be a good opportunity for caffeine addicts to switch to bottled tea instead. I didn’t do this though. Instead, I bought some Japanese instant coffee powder from the supermarket and used that for my daily black coffee needs.

With that said, Chinese coffee shops were excellent, modern, and in abundant quantity. I enjoyed some Moutai flavored lattes from Luckin, which tasted like fruity alcoholic ice cream, and also got iced Americanos fairly often. Interestingly, every coffee shop I visited was espresso-based, so there was no drip coffee or cold brew, and the price was around 20 RMB, which is 3 dollars. You can also ask for “large” Americanos, which cost more, but the only difference is they add more water to the same single shot of espresso.

Package Delivery

In China, you get access to one of the biggest online marketplaces in the world, with amazing products and highly-granular updates on when the package was shipped, by whom, as well as the realtime location status of your delivery driver and his personal phone number.

Once the package actually arrives, though, the process can be quite manual and a little strange. Sometimes the package will be stored in the doorkeeper’s booth, or it’s in a designated room of a hotel or apartment complex, and other times you have to just investigate for yourself where it ended up, especially if there’s multiple mail drop off points in your apartment. Your package will have multiple labels stuck all over it, you’ll have to find it in a sea of other similarly-looking cardboard boxes, and it will be addressed to your Chinese name. For Chinese Americans who hardly ever need to use their Chinese names in any context, you suddenly need to get good at recognizing it!

Etiquette

When I visited China, there was sometimes a culture of stealing seats and people not properly waiting in line, particularly in tourist groups. Although this was less pronounced in Shenzhen and Shanghai, I felt that in general, an event where resources were not allocated according to an official ticket or enforced by security guards could have a problem of people rushing forward to take stuff for themselves. For example, if you go to a theater performance where seats are taken on a first-come, first-served basis, people will run quickly and place their bags on a chair in order to reserve it for themselves and their friends. This truly gets exhausting for me, as a Chinese American, and it’s one of my least favorite aspects of modern Chinese culture. I did notice that sometimes there would be a “line attendant” who would make sure that people aren’t cutting in line or behaving inappropriately, which made my life more comfortable.

Some people also dislike the fact that Chinese people smoke indoors, including at restaurants or even in the hallways of shopping centers, but this was less common in the big cities, and also I don’t personally mind it, since I think it’s amusing and also reminds me of the smoky China smells from my childhood.

Downsides

With everything said and done, what’s bad about Mainland China these days? Here are the main downsides for Chinese Americans who are trying to visit on their own:

English Language: For Chinese Americans whose primary language is English, ultimately, you’ll still need a core of English-speaking friends if you really want to share your inner thoughts with someone, if you’re going through tough times and just really need to bare your heart to someone else, or in case of emergencies where linguistic misunderstandings could be a life-or-death matter.

Western Internet and VPN: A lot of western technology requires a VPN, and you’ll need this for keeping in contact with friends back home or reading western email. It does get genuinely taxing over time to overheat your phone and switch a VPN on and off constantly, with occasional network slowdowns or failures. This limitation is really inconvenient when you absolutely need to check on a certain email, but one benefit is that it encourages you to stop scrolling Instagram and YouTube and to instead spend that time on Xiaohongshu and Bilibili.

Infrastructure not Built for Foreigners: Although I’d say 90% of what I experienced in China was foreigner-friendly, there are occasional workflows and apps that require national ID (shenfenzheng) and in those cases, the foreign person slips through the cracks, and it will be hard for people to take care of you.

China Burnout: Sometimes you just experience “too much China” during your life and need to take a break, like getting tired of people repeatedly stealing your spot in line, not wanting to activate your Chinese language skills for a particular day, or having a desire to eat a particular western food.

The Contradiction of Assimilation and Convenience: Chinese Americans in China often want to learn more about authentic East Asian culture, but the most traditional people and places are not internationalized and don’t have support for English. This creates an inherent contradiction where long-term travel feels better in international hubs like Shanghai, and yet one can accidentally end up being surrounded by too much English and miss out on the ultimate goal of reconnecting with East Asian roots.

Conclusion

The quality of life in mainland China is very high and almost unbeatable for those who are willing to take the plunge. Asian Americans would do well to try slow-traveling throughout the country on their own terms, not just cultural tourism, not just visiting family members, but experiencing the daily life of various cities to see the different patterns in regional life, perhaps in the hopes of finding a location that’s perfectly suited to one’s own tastes. I am looking forward to my next visit to the mainland, and I hope that you too, give it a try!

If you liked this article, check out my previous post on Japan as a destination for Asian Americans, my Twitter account, and YouTube videos.

reading this filled me with happiness and hope. thank you.

>Although America has Chinatowns and Chinese communities, I would say that the best Chinatowns do not surpass the beauty of even a 4th Tier city in China.

Yep and its a testament to how well-developed even 4th tier cities are.

>Downsides: With everything said and done, what’s bad about Mainland China these days?

Social obligation here is much stronger ahaha. Social relationships as a whole can be more intricate here. BUT it always means friends here are much more willing to help - even at slight risk to themselves.